Review: Here I Stand

boy bandsthe wicker cardall aboard the succubusmost mustysmallpox

00

Quinns: Matt? I need a second opinion on this beret. Hey, what'choo guys doing in this basement?

Thrower: INFIDEL! Remove that at ONCE! Can’t you see this is a Holy Place?

Quinns: I did wonder who all the menacingly hooded, chanting figures were.

Thrower: This is a shrine dedicated to the worship of the one true wargame mechanic: the card-driven game. And tonight, from our multitudinous pantheon, we are worshipping the many-headed and many-handed goddess. Mistress of lies and deceit, changer of the ways and the patron succubus of politicians: Here I Stand.

Quinns: Well yes. You’re right in front of me.

Thrower: SHHH! In the constellation of card-driven games, the many-headed goddess is third in line behind Washington’s War, a redesign of the game which originated our religion, and Twilight Struggle which perfected it. There are many reasons we exalt it so. One is that Here I Stand is a game about the wars of the religious Reformation in Europe and it inspired us to build a reformation of our own, against the musty and ancient diktats of hex and counter gaming and toward a more card driven future!

Acolytes: TOWARD A MORE CARD DRIVEN FUTURE!

Quinns: That’s … tuneful. Card driven-wargames? That sounds familiar, actually.

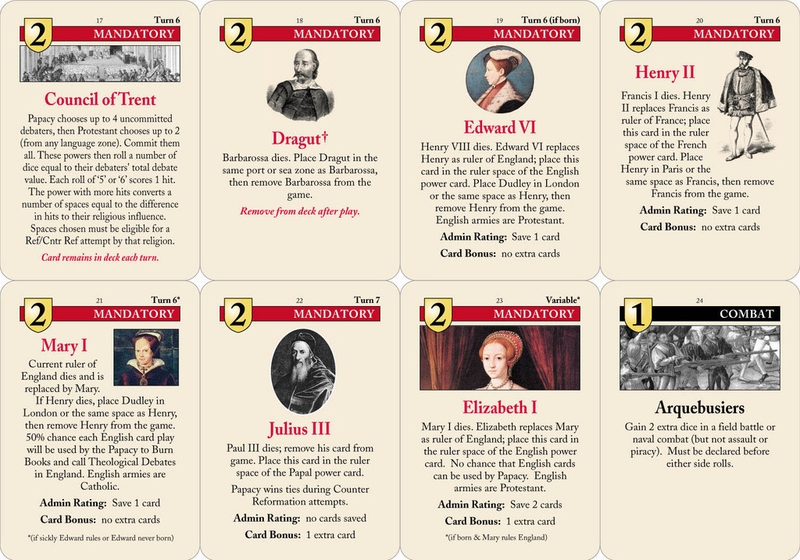

Thrower: You still get units to manoeuvre on a map, but you also get a hand of cards which are a mixture of numeric values and historical events tied to one of the sides in the conflict. Often, you get both on the same card so if you get one of your own events you choose between playing it for the event effect, or cashing in the points and using them to move units. This creates a game within a game, as you’re no longer just planning strategy on the board, but managing a hand and calculating the optimal mixture of points and events. It’s magnificently frustrating.

Quinns: Sounds... great?

Thrower: Ah, it is! It’s amazing how easily it crams living, breathing history into a game in a manner that cardboard chits alone can’t manage. In Here I Stand there are cards for the invention of the Printing Press, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel and many other key events of the Reformation. Have you ever played a hex and counter game?

Quinns: Yes, actually, I--

Thrower: They focus solely on the military aspects of conflict, nothing else. Only a card driven game can give you so much supporting detail. And there’s more: when you spend cards for points instead of events, those points are just an abstract currency to do stuff. You could just move units. But in most card-driven games you can use them for other things like spreading political influence over the map. To do that, you also need troops in the vicinity, leading to a glorious combination of mutually supporting mechanics: cards, troops and politics, the holy trinity.

Acolytes: CARDS! TROOPS! POLITICS! THE HOLY TRINITY!

Quinns: Oh wow. You guys are like the most poorly focus tested boy band ever. What’s so special about Here I Stand in particular?

Thrower: The designer, Ed Beach, did two new and wonderful things with the card driven format. Firstly, he made inter-player politics jump off the cards and onto the table. It’s not the first card-driven game that works with more than two, but it is the first to have a special phase dedicated to negotiation and deal making.

Everyone draws from one deck, so the England player might find himself with a hand of cards playable by the Papacy or the Ottoman Turks. He could just play them for the points, but he could also negotiate with those players to get things he wants. Like a divorce for Henry VIII for example, or a distracting attack on the Austrian Empire.

Quinns: So it’s a game that revolves around making and breaking alliances?

Thrower: Not at all. The deals are fascinating because they’re often crucial in determining how a turn plays out, but are non-binding.

So players desperately make deals to lever as much advantage as possible, and then sweat over whether their opponents will keep their side of the bargain. But they’re usually over single cards so don’t result in long-term alliances and aren’t allowed to dictate the course of the whole game. The result is a title that does diplomacy better than Diplomacy does diplomacy.

Quinns: Have you forgotten your medication again?

Thrower: No! I mean yes, but LISTEN! The other innovation is that Ed realised those points aren’t limited to moving troops and political influence. They could represent absolutely anything in terms of national resources. So in Here I Stand, the western European players can use them to send treasure seekers to the New World, the Turks can use them to fund piratical raids and the religious powers can instigate debates with each other, occasionally resulting in my favourite part of the game: the burning of heretics.

Acolytes: BURN THE HERETICS!

Quinns: SHUT UP!

Thrower: There’s more besides, but it should give you a sense of the rich flavour of the past, the enormity of the history that’s communicated by this game. Between the diplomacy, the library of card effects and all the different ways you can spend operations points every game is plausible alternate retelling of the Reformation. The key events might not happen in the same order as they actually did, but that doesn’t invalidate the gripping realism of the tale you’re telling. It isn’t just a game, it’s the best, liveliest, most absorbing history lesson you’ll ever have. Do you know much about the Reformation?

Quinns: I, er … no.

Thrower: You will after just one play of Here I Stand. The historical evocation of the play itself is ably supported by the game components. The current edition has a mounted map, and the cards are furnished with well-chosen snippets of period art to add to the effect. The whole thing is just an incredible re-creation of one of the pivotal passages in European history.

Quinns: So it’s something you play all the time?

Thrower: Sadly, no. You don’t get all that detail for free: you pay for it in complexity and time. The rulebook is forty-eight text dense pages, although people already familiar with card-driven games can skim some of it. And you can save more pain by only learning the special rules pertinent to the power you’re playing – you won’t need the others. And to play you’ll really need to find five other people since it works best with a full complement, and either eight hours of face-to-face time or eight months of play by email time. Have you ever played a game via email?

Quinns: I, er … no.

Thrower: I see. Well then, I think it best if we perhaps steer you away from the object of our veneration and toward this curtain in the corner. Come. It is time to keep your appointment with … The Wicker Card.

Acolytes: THE WICKER CARD!

Quinns: O God! O Jesus Christ!

Thrower: We sacrifice to the dark gods of gaming, so our reformation might succeed. Animals have not been enough. Instead we must offer the right kind of adult: one who is a virgin to historical gaming, a has been foolish enough never to engage in historical research.

Quinns: WAIT! I remember where I've seen these card-driven things before! They're in 1960: The Making of the President and Labyrinth: War on Terror! I've played some of these!

Thrower: Oh, balls.

Acolytes: OH, BALLS!

Quinns: Actually, I've got to tell you, I'm not 100% sold on the idea. To me, one of the strengths of big, complicated wargames is their ability to immerse you utterly in the role of a leader. With card driven systems you end up feeling like an overworked Time Lord, delaying discoveries, accelerating accidents, and puzzling over the shards of the time-space continuum you've been dealt. You're not playing anyone anymore.

Thrower: …Mr. Smith?

Quinns: Yes, Matt?

Thrower: We should talk.

End of Part 1.